Family Stories

Family Stories

» Show All «Prev «1 ... 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 ... 44» Next» » Slide Show

1922 Sir Albert Gooderham’s Contribution to the Insulin Story

During the first two decades of the 20th century, several investigators prepared extracts of pancreas that were often successful in lowering blood sugar and reducing glycosuria in test animals. However, they were unable to remove impurities, and toxic reactions prevented its use in humans with diabetes. In the spring of 1921, Frederick G. Banting, a young Ontario orthopedic surgeon, was given laboratory space by J.J.R. Macleod, the head of physiology at the University of Toronto, to investigate the function of the pancreatic islets. A student assistant, Charles Best, and an allotment of dogs were provided to test Banting’s hypothesis.

Success with purification was largely the work of J.B. Collip. Yield and standardization were improved by cooperation with Eli Lilly and Company.

One Event—Three Versions

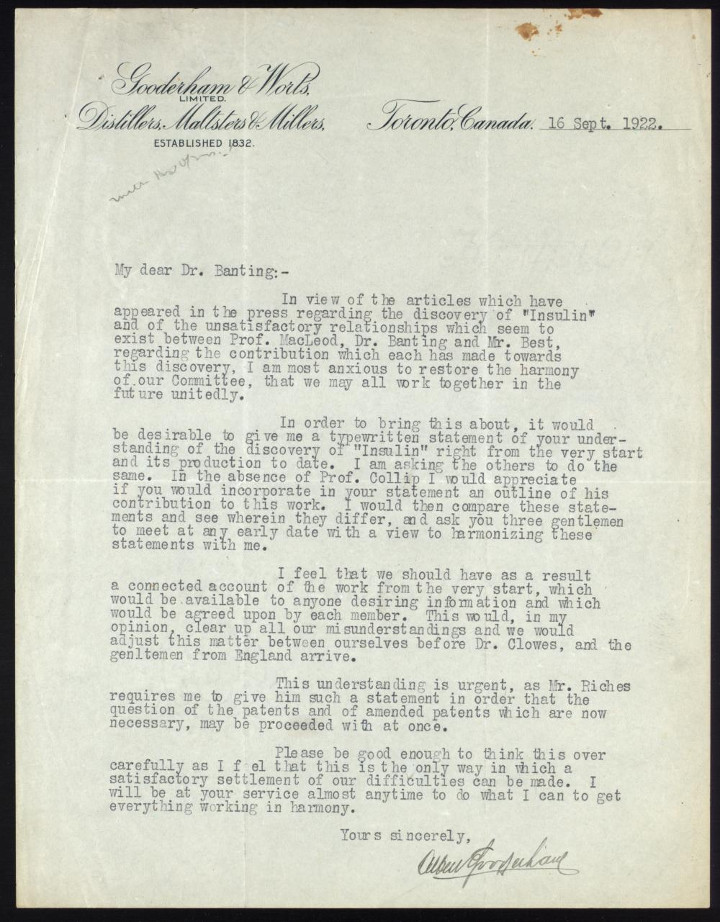

At this point entered Colonel Albert Gooderham, prominent member of the Board of Governors, patron of the Connaught Laboratories, and chairman of the Insulin Committee. Anxious to end the growing dispute, he decided to intervene. In September 1922, he asked Banting, Best, and Macleod to prepare their own understandings of the discovery of insulin. Each was asked to outline Collip’s contribution. Gooderham did not write to Collip. He planned to compare the statements and then meet with them to clear up all misunderstandings and prepare one agreed-on history.

Col. Albert Gooderham, solicits accounts of the discovery of insulin from Banting, Best and Macleod. https://heritage.utoronto.ca/exhibits/insulin They each respond with a written submission. https://insulin.library.utoronto.ca/islandora/object/insulin%3AL10003

Had Gooderham sought comments from Collip, he might have received something like the feelings he expressed in a letter to a friend. Probably written in 1923, Collip said: “There are some people in Toronto who felt that I had no business to do physiological work…. The result was that when I made a definite discovery my confreres instead of being pleased were quite frankly provoked that I had had the good fortune to conceive the experiment and to carry it out. My own feelings now in the matter are that the whole research with its aftermath has been a disgusting business”

Apparently, Macleod privately changed his appraisal of the discovery when it appeared that a Nobel Prize was a possibility. Two months after his response to Gooderham, he told the visiting August Krogh that Banting and Best would have gone off on the wrong track without his advice and guidance.

When the Nobel Prize was awarded to Banting and Macleod for the discovery of insulin, it aggravated the contentious relationship that had developed between them during the course of the investigation. Banting was outraged that Macleod and not Best had been selected, and he briefly threatened to refuse the award. He immediately announced that he was giving one-half of his share of the prize money to Best and publicly acknowledged Best’s contribution to the discovery of insulin. Macleod followed suit and gave one-half of his money award to Collip. Years later, the official history of the Nobel Committee admitted that Best should have been awarded a share of the prize.

Banting was furious when he learned that Macleod was to share the Nobel Prize and said he would not accept the award. Gooderham, who knew the whole story, told Banting he must think of his obligations to Canada and science. How would it look if the first Canadian to receive this honor turned it down because of a difference of opinion about the Prize? Banting changed his mind. He decided to share the money award and the credit with Best. Macleod was on a ship returning from England when he heard the news. A few days after landing in Montreal, he telegraphed Collip and asked him to share his half of the prize money. Collip accepted. Macleod told the press “it is teamwork that did it”. Banting and Macleod were each awarded an honorary Doctor of Science degree by the University of Toronto on November 26. Macleod was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society of London in 1923. Banting had to wait until 1935 for this honour.

http://www.clinchem.org/content/48/12/2270.full#sec-24

Compiled by George Gooderham (from web sources provided) after his daughter received a $100 bill from her “Grandy” for her 16th birthday. The bill depicts the story of insulin: https://www.bankofcanada.ca/banknotes/bank-note-series/frontiers/100-polymer-note/

1922 Sir Albert Gooderham’s Contribution to the Insulin Story

Banting, Best, and Macleod each had their own understandings of the contributions leading to the discovery of insulin. Colonel Albert Gooderham, prominent member of the Board of Governors, patron of the Connaught Laboratories, and chairman of the Insulin Committee, sought to sort it out.

| Owner of original | http://www.clinchem.org/content/48/12/2270.full#sec-24 |

| Linked to | Connaught Laboratories (now Sanofi Pasteur), Toronto, ON, Canada; Sir Albert Edward Gooderham, Sr. |

» Show All «Prev «1 ... 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 ... 44» Next» » Slide Show